Contents

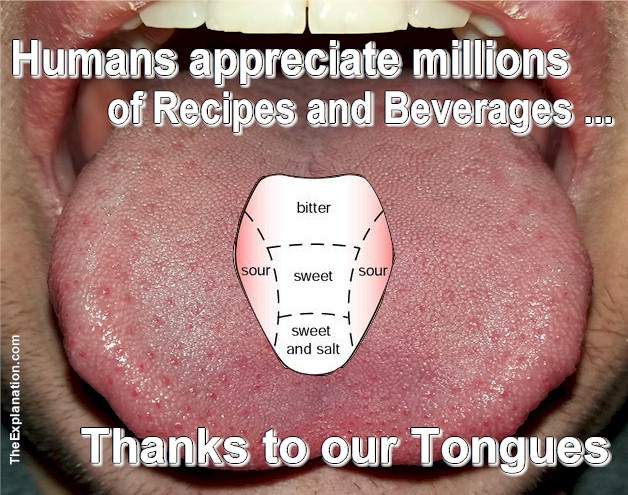

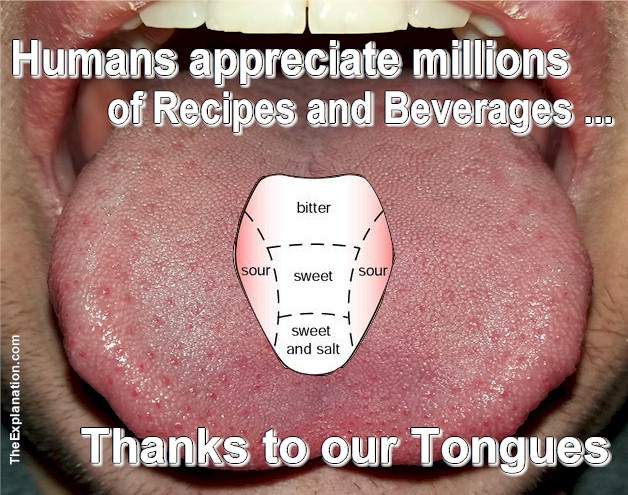

Tongues and taste buds allow humans to taste and appreciate the nuances of all types of ingredients in recipes and beverages from around the world. Plus the human ability to vocalize and speak over 6000 languages.

With hundreds of thousands of ingredients worldwide used for recipes and beverages, only our tongues allow us to appreciate and enjoy the textures and flavors.

Our tongues, along with the palate and insides of the cheeks that we examine in a mirror, harbor 10,000 taste buds. Galacti and the doctors inform us that, contrary to what was previously thought, tongues do not have distinct zones for sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and the pleasantly savory taste known as umami, which allows us to taste the amino acid L-glutamate in cheese and wheat.

(chapter 8.3)

Instead, taste bud cells have different sensitivities for these flavors. These tastes allow us to savor food, which is key in the experience of eating, and also to detect when something doesn’t taste right, which is usually important for survival. In this way, they play a part in sustaining the body.

However, our tongues together with our lungs, trachea (windpipe) and “voice box,” serve an even more significant purpose.

The car accident victim is put on a ventilator which helps her to breathe, but not to speak. Even in an anesthesia-induced sleep, the patient cannot make any kind of sound we recognize as a human voice. She is incapable of speaking any of the forty-four phonemes (vowel and consonant sounds) of the English language or the twenty-seven phonemes of the Spanish language. These simple sounds enable the doctors and nurses to express and trade their knowledge.

The voice is a subtle mixture of sounds from the throat, mouth and lips.

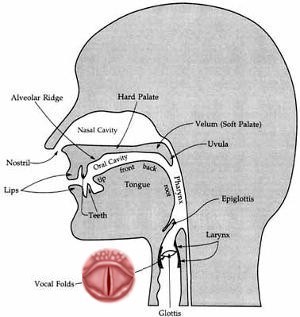

The doctors substitute the anatomical diagram above for the MRI image of the human respiratory/vocal system, and we follow the breath through the mouth, nose, and sinuses, then down the pharynx and into the lungs.

As the breath comes back up through the larynx and vocal folds, we are invited to speak a single word: “hello.” The vocal folds, which are delicate tissues, are brought close together as breath pushes up from the lungs and makes the vocal folds vibrate.

It also makes the tongue and lips move to produce “hello.” We notice the pronunciation, “he-loh.” The lips, tongue, and soft palate (or roof) of the mouth form the sounds. As we say “hello,” the tip of our tongue touches the soft palate on “he,” and then extends straight out between the teeth on “loh.”

That simple word might not sound earth-shattering (pun intended), considering the roughly one million words in the English language (an estimate made by Merriam-Webster) and the 600,000 words in the Japanese language. However, consider the importance of “hello” as a greeting and an expression of friendliness.

Thomas Edison popularized the word as a telephone greeting during his experiments in the nineteenth century and used it as part of his method of conveying knowledge. Galacti notes that if Edison, dubbed the Wizard of Menlo Park, thought “hello” was significant, then perhaps we should give it another look.

Think of the twelve to twenty breaths per minute that are required to supply the air to make the vocal folds vibrate. The blood cells, which carry oxygen, also participate. Think of the lung capacity, the size of a tennis court compressed to fit underneath your ribcage, that allows you to breathe and speak. We ponder that this system works so precisely every day.

It is something that we all take for granted, except of course when we have to give a talk in public! Our diaphragm and abdomen also play a role in making our voices sing with passion, authority, intelligence, and other emotions. An iPod plays music that is amplified by speakers.

A Hawaiian hula song echoes through the operating theater and is followed by a black gospel singer belting out a hymn. We move to the music and lift our voices. Galacti points out that this ability to sing and speak has allowed humans to transmit knowledge, starting with the Epic of Gilgamesh as the earliest known oral tradition story.

The role of singer/storyteller has been an honored one in many cultures, and even today in our global society dominated by the electronic and written word, there are people such as the Inugguit in Greenland.

The Inugguit are a people that speak the threatened language of Inuktun, which contains words formed by murmurs and moans that can be up to fifty letters long! They still maintain their oral tradition.

We wonder at the history of speech. When were the first syllables or words spoken? Were they spoken by the ancient Chinese or by Indus Valley dwellers? Linguists, historians, and anthropologists have various theories on the origin of language, but no one knows for sure how language began or which culture produced the first protowords.

For us, it is simply enough to ponder that speech exists at all. We can say hello and goodbye in many different languages: hola and adios in Spanish, konnichi-wa (literally meaning “good afternoon” or “good day”) and sayonara in Japanese, sawasdee for both hello and goodbye in the Thai language, bonjour and au revoir in my Paris home, and zdravstvujtye and dosvedanya in Russian.

We can say “Come here, Watson, I need you,” as another famous inventor, Graham Bell, did. Our brain is responsible for our speech, more so than our vocal folds, lungs, or the oxygen in our cells, but everything works together to produce “hola” and “goodbye.”

We ponder language, one of the hallmarks of human beings. As we’ve seen, the ingredients of life come together to form the basis for biological human beings. To take this another step, the separate ingredients of the respiratory and vocal systems—the lungs, trachea, pharynx, larynx, palate, lips, tongue, and the blood carrying oxygen—come together along with the brain to make language possible.

Someone feels his jawbone, which is making a clicking sound. We are drawn to the uniqueness of the jaw. Although mammals, amphibians, and reptiles have jaws for eating, biting, and making various noises such as barking, the human jaw is equipped to aid in speech. It is the only bone in the skull that can move freely. This encourages us to examine the human skeleton.

This post is an excerpt from chapter 8.3 of Inventory of the Universe.

The Explanation Blog Bonus:

Today I have a couple of videos, this first one is for the kiddies, but we can all learn something about tongues.

This second one is interesting in that it only credits human tongues with 4 tastes. I’ve noticed that descriptions regarding properties of tongues, depending on authors, are not always the same. In spite of the differences our tongues make eating all the varieties of food a very enjoyable necessity.

Dig Deeper into The Explanation

Join The Explanation Newsletter to stay informed of updates. and future events. No obligations, total privacy, unsubscribe anytime, if you want.

Online Study Courses to Unlock Bible meaning via Biblical Hebrew… with no fuss. Free video courses that put you in the driver’s seat to navigate the Bible as never before. Join now

The Explanation series of seven books. Free to read online or purchase these valuable commentaries on Genesis 1-3 from your favorite book outlet. E-book and paperback formats are available. Use this link to see the details of each book and buy from your favorite store.

Since you read all the way to here… you liked it. Please use the Social Network links just below to share this information from The Explanation, Tongues Taste Worldwide Recipes and Talk over 6000 Languages